It’s been a while! Dr. Small Talk has been up to her ears in other writing obligations and teaching, so thanks for your patience. Today I’m pleased to offer the third and final installment in my series about how the First World War and its aftermath—arguably more than any other event—shaped the modern Middle East. You might recall that in Part I, we spoke about how the war transformed the Zionist movement and wed it to the British empire; Part II examined the imperial logic that underlay French and British attitudes toward the Ottoman Empire, which was dismembered and divided up into new League of Nations mandated territories. We also spoke about how the Mandate system, posing as a form of tutelage for “less advanced” nations, offered the old business of colonial domination a new lease on life in an age when self-determination was (at least rhetorically) very much in vogue. Today we’ll finish the story by looking at how a nascent democratic Arab state with a liberal constitution drafted by a congressional assembly was squashed by the French with British acquiescence - a story that Elizabeth Thompson details in her aptly-titled book, How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs.

When we left off, Prince Faisal—son of Sherif Hussain of Mecca, ruler of the Hejaz and leader of the Arab Revolt—was at the Paris Peace conference lobbying for the Allies to fulfill the conditions outlined in the secret correspondence between his father and Henry McMahon, acting on behalf of the British Government. If you recall from Part I of this series, though the British tried their best to defer the question of boundaries and keep their promises vague, they did eventually agree to supporting an independent Arab state following the war in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire — excepting Lebanon and the oil-rich districts of Baghdad and Basra, which the British were insistent on occupying to secure their oil deposits.

Yet there were other wartime agreements that complicated this pledge: the Balfour Declaration, of course, but also the secret agreement with France (i.e. Sykes Picot Agreement) that parceled up the post-war Middle East into French and British zones of influence. Such nakedly imperial ambitions were initially hard to square with Woodrow Wilson’s famed 14 points, which called for an end to secret agreements, a thorough reevaluation and adjustment of colonial claims, and stipulated that non-Turkish nationalities under Ottoman rule should be given “absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.” At the Paris Peace Conference, Wilson and the Americans furthered wrinkled feathers by deciding to dispatch a delegation to the Arab lands to ascertain the wishes of those who lived there regarding their future. The nerve!

Led by by Oberlin College president Henry C. King and Chicago businessman Charles R. Crane, the delegation toured Syria and Palestine for about five weeks during the summer of 1919. The commission’s report was delivered to the Paris Peace Conference in August 1919, but it was suppressed for reasons detailed below, and not published until 1922. By this time, the Mandate system was more or less in place, Britain was in charge of Palestine, and the United States had retreated from international diplomacy by refusing to join the League of Nations. The commission’s warnings sound extraordinarily prescient from our vantage point, but they were not the product of any remarkable insight or genius. They were rather the result of doing something that many Western politicians and media types have a hard time with: asking people how they feel and what they want, and taking those opinions seriously.

Let’s look at some of the key passages about Syria and Palestine. The report began by stipulating that the proposed mandate system must differ in substantive terms from the old business of empire, which testifies to just how anxious many were that it would not:

Second, the commission recommended that a new Arab state emerge from the Arabic-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire, and that the unity of Greater Syria—meaning the territory that today makes up Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Israel/Palestine—should be preserved. It made no sense to them trying to create artificial borders between peoples that for 400 years had been part of the same state, and that held much culturally in common:

Next, the commission recommended that Emir Faisal should serve as the leader of the new Arab state, in accordance to the wishes of the General Syrian Congress, and that the state should be a constitutional monarchy administered on a decentralized and democratic basis. This, the commission stated, was the overwhelming preference of those that they interviewed. Taking the wishes of those people seriously necessitated, they argued, a “serious modification of the extreme Zionist programme for Palestine.” Here are the juicy bits:

The Commission’s report was unequivocal: There was simply no way to fulfill the Balfour Declaration’s stated aims of creating a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine without violating the supporting clause that “it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing nonJewish communities in Palestine.” It was impossible to square that circle. Furthermore, the report argued, transforming Palestine into a Jewish state against the wishes of 90% of its population would be a gross violation of the principle of self-determination. Note that there is mention here, already in 1919, of the likelihood of dispossession, though the committee envisioned it would take place predominately via purchase rather, as it happened, through war (more on this coming soon). Finally, the commission noted that the anti-Zionist sentiment was both perfectly comprehensible and unlikely to abate, and cautioned the Peace Conference to commit itself to a course of action that was so deeply unpopular. Implementing the Zionist program, the report emphasized, could only be achieved through overwhelming armed force:

Given the nature of these recommendations, it is not surprising to find that the King-Crane Commission recommendations were suppressed and ignored. Still, we should take a closer look at the road not taken before dealing with the final settlement.

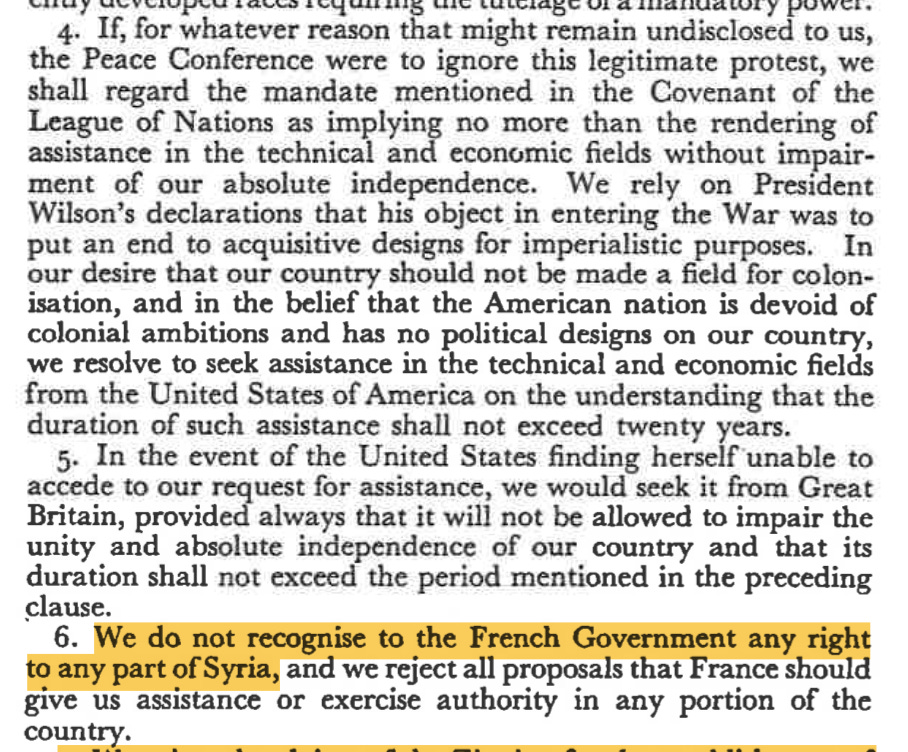

About a month before the King-Crane Commission submitted its report to the Paris Peace Conference, the delegates who had been gathered in Damascus to establish a new united Arab state (many of whom appear in the image above) published a declaration of principles. The document called for a fully sovereign state in Greater Syria, headed by Emir Faisal, and “based on principles of democratic and broadly decentralized rule which shall safeguard the rights of minorities.” The delegates further stipulated that the Arabs were no less advanced than other emerging nations, and objected to the imposition of any sort of tutelage through the mandate system. However, if the international powers were insistent on subjecting them to such tutelage, the General Syrian Congress had some strong opinions about their overseers:

You got that right: they preferred an American mandate because they found the US “devoid of colonial ambitions.” It is not that the US was not an empire at this stage—the occupation of the Philippines began in 1898, not to mention imperial forays into the Caribbean, Latin America, and the work of westward expansion—but the US had no imperial presence in the Middle East at this time. In the event that the Americans could not assume the mandate, the strong preference was for Great Britain; and for God’s sake, they pleaded, please don’t send the French.

The Syrian Congress rejected the premise of Zionism and the prospect of partitioning Palestine from the rest of the Arab lands, while stipulating that “our Jewish fellow-citizens shall continue to enjoy the rights and to bear the responsibilities which are ours in common.” Elizabeth Thompson’s book includes the full text of the constitution that was adopted in March 1920 if you want to take a look; it arguably represents the most liberal constitution ever enacted in the region to this date. And why not? The 1920s represented the apex of what historian Albert Hourani called the liberal age of Arab intellectual and political history.

But the independent Arab state never had a chance. After the death of Woodrow Wilson and the US’s refusal to join the League of Nations, Great Britain found herself in a precarious diplomatic position. Not only were the Americans out of the game, but the Russian Revolution had robbed Britain of another key ally. They were left with the French, and France really wanted their spoils of war.

2.5 million British troops were stationed throughout the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of the war, but they gradually pulled out of Syria and Lebanon and stopped supplying Faisal’s Arab army. The French did not recognize the independence of the fledging Arab state, and gave Faisal an ultimatum to accept the imposition of a French mandate per the League of Nations determination. After some intense back and forth, which you can read more about in Thompson’s book, the French marched on Damascus and quickly defeated Faisal’s Arab army, which barely had enough ammunition for a single gun fight. If you go to the Imperial War Museum in London, you can find the flag used in this fateful confrontation.

Looks a bit familiar eh? Someday I’ll write about flags but this is not that day.

So what happened next? To make a long story short, after Faisal’s forces were defeated by the French, his brother Abdullah gathered a small army and started marching north from the Arabian peninsula to avenge his brother. The British intercepted them in what’s now Jordan, and offered an ingenious solution to keeping all their allies happy: the partition of the Mandate for Palestine into two sections with the river Jordan as the boundary would allow the Jewish national home to develop west of the river, and establish a new political entity called Transjordan (or today, just Jordan) to the east. Abdullah could be king. And poor Faisal wasn’t left out to dry either. At a meeting in March 2021 in Cairo, his British patrons offered him the kingship of Iraq (which also fell under a British mandate) as a consolation prize. Both brothers duly accepted. Faisal remained King of Iraq until his death in 1933. He was succeeded by his son and grandson, who was overthrown in a military coup in 1958.

Abdullah had better luck, at least for a while. He ruled Jordan throughout the interwar period and colluded with the Zionist Executive to occupy the portions of Palestine that (per the 1947 UN partition plan) were designated as the future Arab state. He was assassinated at al-Aqsa mosque in 1951 by a Palestinian who was likely working with the powerful al-Husseini family. His grandson, Abdullah II, still rules Jordan to this day.

And that, my friends, is how we went from a united Arab kingdom to the Syrian Arab Republic to the the nation-states of today’s Middle East. I’ll be back soon!

So helpful and cogent, can’t thank you enough!