Zionism, World War I, and the Imperial Frame: Part I

How WWI supercharged Zionism and wed it to empire

Over the last several years, we have seen the emergence of an intense debate about the nature of Zionism. Is the movement an expression of Jewish nationalism and the legitimate right to self-determination? Or a European, settler-colonial conquest of Palestine hellbent on dispossessing/eliminating its indigenous inhabitants? The very long story short is Zionism is a Janus-faced movement that contains elements of both, and just as importantly, Zionism has not always meant the same thing as it does today. Understanding these ambiguities is crucial in this moment because the departures of Zionism from the standard settler-colonial model should also indicate that the liberation tactics favored by 20th century anti-colonial nationalist movements are unlikely to succeed in this case, or, more darkly, will ‘succeed’ in ways that could hardly count as emancipatory (I spoke about this in my conversation with Samantha Rose Hill if you’re interested).

Today’s newsletter aims to fill in some important context by looking at how the First World War transformed the Zionist movement. It was in this moment that Zionism first became linked to European imperialism, the support of which was indispensable for the achievement of its aims. It is not that there was nothing problematic about Zionism prior to this point, or that it didn’t entertain fantasies of Palestinian dispossession, but that it was only by marrying itself to the imperial cause that such goals became actionable on a large scale. Given the immensity of the topic, I can only start to scratch the surface today but let’s give it a go.

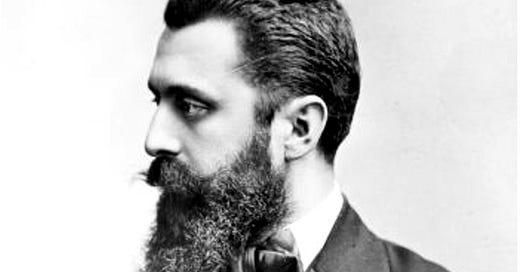

The early Zionist movement was divided into several different factions, each advancing their own, often oppositional, stance on the movement’s ends and means. There were those (like the secular Theodor Herzl) who regarded Zionism chiefly as a political solution to the problems of antisemitism and Jewish minority status in Europe. There were others (most famously, Ahad Ha-am) who thought of Zionism in cultural terms and who aspired not for statehood but for a “cultural center” in Palestine. This was crucially important because the unprecedented possibility of Jewish assimilation into varying national communities was erasing any sense of Jewish cultural identity outside of that overseen by the religious establishment.

Theodor Herzl, widely regarded as the founder of political Zionism

Then there were the religious Zionists like Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook who broke with normative Orthodox views to embrace Zionism as a movement steeped in messianic hopes (prior to WWII, the Orthodox establishment opposed Zionism on the grounds that—by trying to reestablish a political entity in Palestine before the messianic era—Zionists endeavored to usurp God’s redemptive power). Far more important in the early days were the Labor Zionists who attempted a synthesis between socialism and Jewish nationalism. Closely associated with the creation of kibbutzim and the regeneration of the Jewish body (and particularly Jewish masculinity) vis-a-vis the embrace of agricultural labor, it is this group that is most mythologized in Zionist history. It was also this faction that dominated interwar Zionism in Palestine and that ruled Israel in one form or another until the electoral victory of Menachem Begin in 1977. And finally, there were the General Zionists (like Chaim Weizmann, whose conversation with Humphrey Bowman I covered earlier), centrists who functioned something like the Joe Biden of early Zionism.

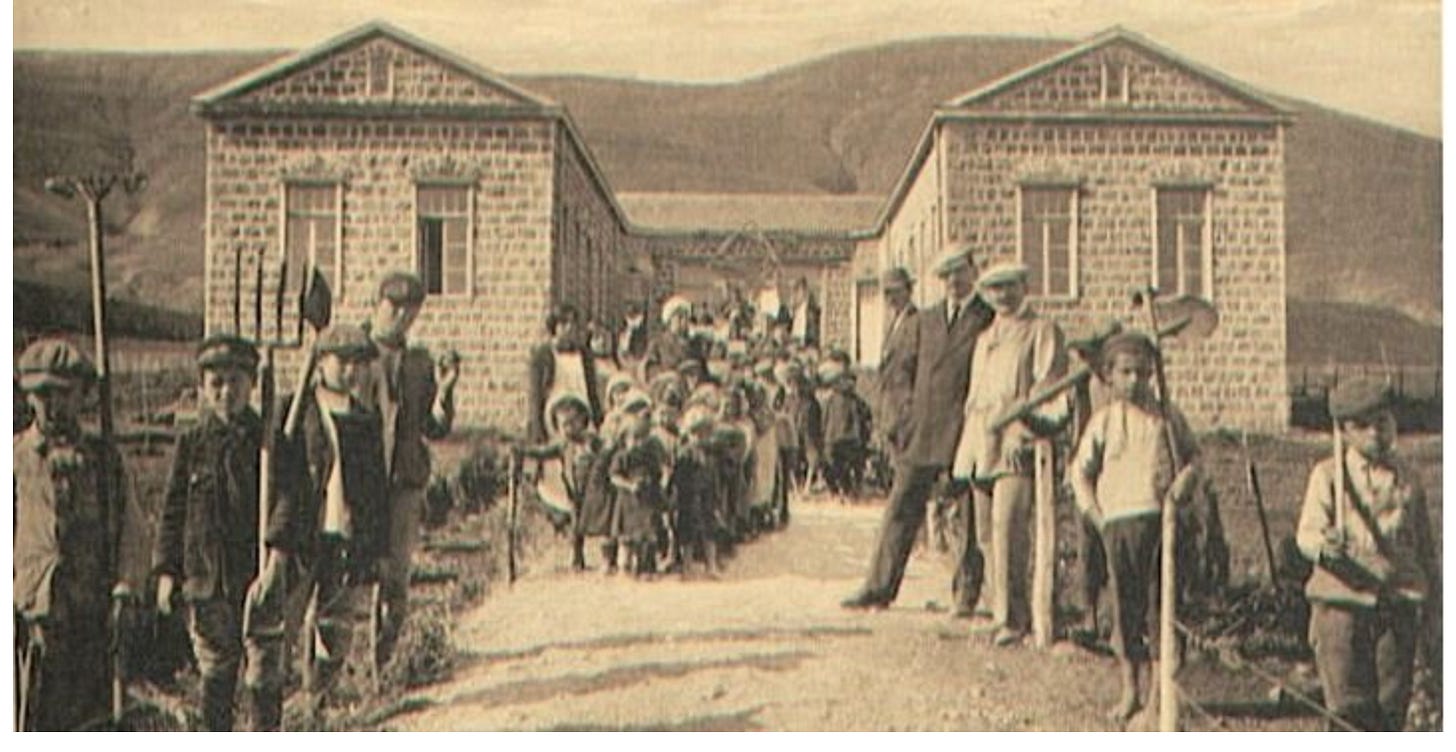

These factions advanced different ideas about almost everything, including whether or not Palestine was the only option for establishing a Jewish homeland. Palestine won out for a variety of reasons, but questions remained about the best means to achieve the movement’s aims. For many years Herzl attempted to secure a charter from the Ottoman Sultan, who rebuffed the idea of signing Palestine over to the Jewish people. Labor or ‘practical’ Zionists advanced a different strategy, namely, establishing Jewish settlements in Palestine on a small-scale with the hope of their eventual expansion. It was this group that powered the Second Aliyah, which lasted from 1904-1914 and brought about 35,000 Jews, chiefly from Eastern Europe, to Palestine.

A photo by Ya’acov Ben Dov of a Second Aliyah agricultural community ~1911

Everything changed, quickly and dramatically, when the First World War began. Jews fought in the war in unprecedented numbers and regarded the war experience as a way to prove their full worth as citizens (I wrote about this a looooong time ago if you want to hear from 2008 not-yet-doctor-small-talk). Some Zionists in Palestine even returned to their European home countries to fight! For many central and eastern European Jews, the war proved a bitter disappointment. Not only did their willingness to die for the fatherland not eliminate antisemitism, it seems to advance it. Zionism emerged in this context as the only option, a point brilliantly relayed by Avigdor Hameiri’s The Great Madness, which ranks among the best (though largely unknown) novels of the First World War.

The situation in Palestine was fraught in different ways. The entire country faced famine and an increasingly dictatorial and paranoid government. Jews who were native to Palestine, like Yehuda Burla (who I’ve written about here), fought in the Ottoman army and even those who were Zionists tended to see no conflict between that commitment and their future as Ottoman citizens. As Eyal Geno and Yuval Ben-Bassat note in Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule, "Zionism was a cultural form of nationalism, an emerging identity which did not clash with their loyalty to the Ottoman state." However strange to our ears today, many Zionists regarded the future of their movement as unfolding within the Ottoman Empire — not in opposition to it. And this was true of European Jewish immigrants as well, which is one reason why David Ben Gurion spent the war years studying law in Istanbul.

In November 1914 the Ottomans joined the Central Powers for reasons I both know and yet struggle to understand, reportedly stemming from their own feelings of insecurity if they remained neutral (do you ever lay awake at night and imagine what the world would look like if the Ottoman Empire never entered the war or is it just me?). As the war dragged on and the Allied Powers found themselves bogged down on the Western front, an idea emerged to open up a new front by taking the war to the Middle East. This is where the famous Lawrence of Arabia comes in. Lawrence was sent to advise Sherif Hussein of Mecca, the semi-autonomous ruler of the western region of the Arabian peninsula, as he raised an army to fight the Ottomans. We should mention that the British plan to foment an Arab revolt occurred in a context of Orientalist fantasies about noble Arabs overthrowing the yoke of Turkish despotism and reestablishing an Arab Caliphate. Fun times.

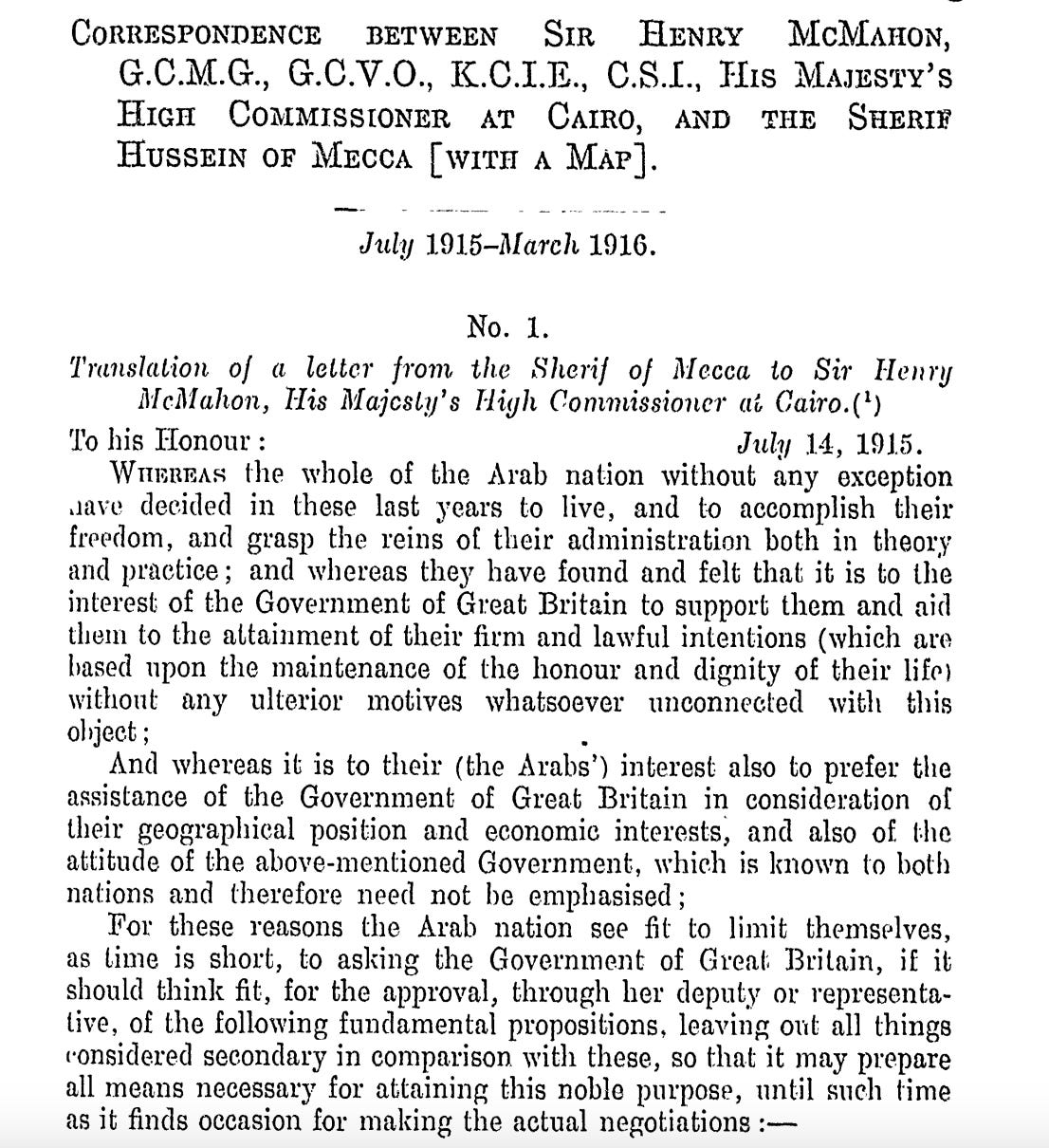

In a famous series of letters from 1915-16 (first made public by George Antonius in his 1938 classic, The Arab Awakening) the British promised Sherif Hussain that in exchange for his help leading a rebellion against the Ottomans, they would support the creation of an independent Arab state after the war. Let’s take a look at one of the most important letters, wherein Sherif Hussein outlines his position and asks for British support of Arab independence.

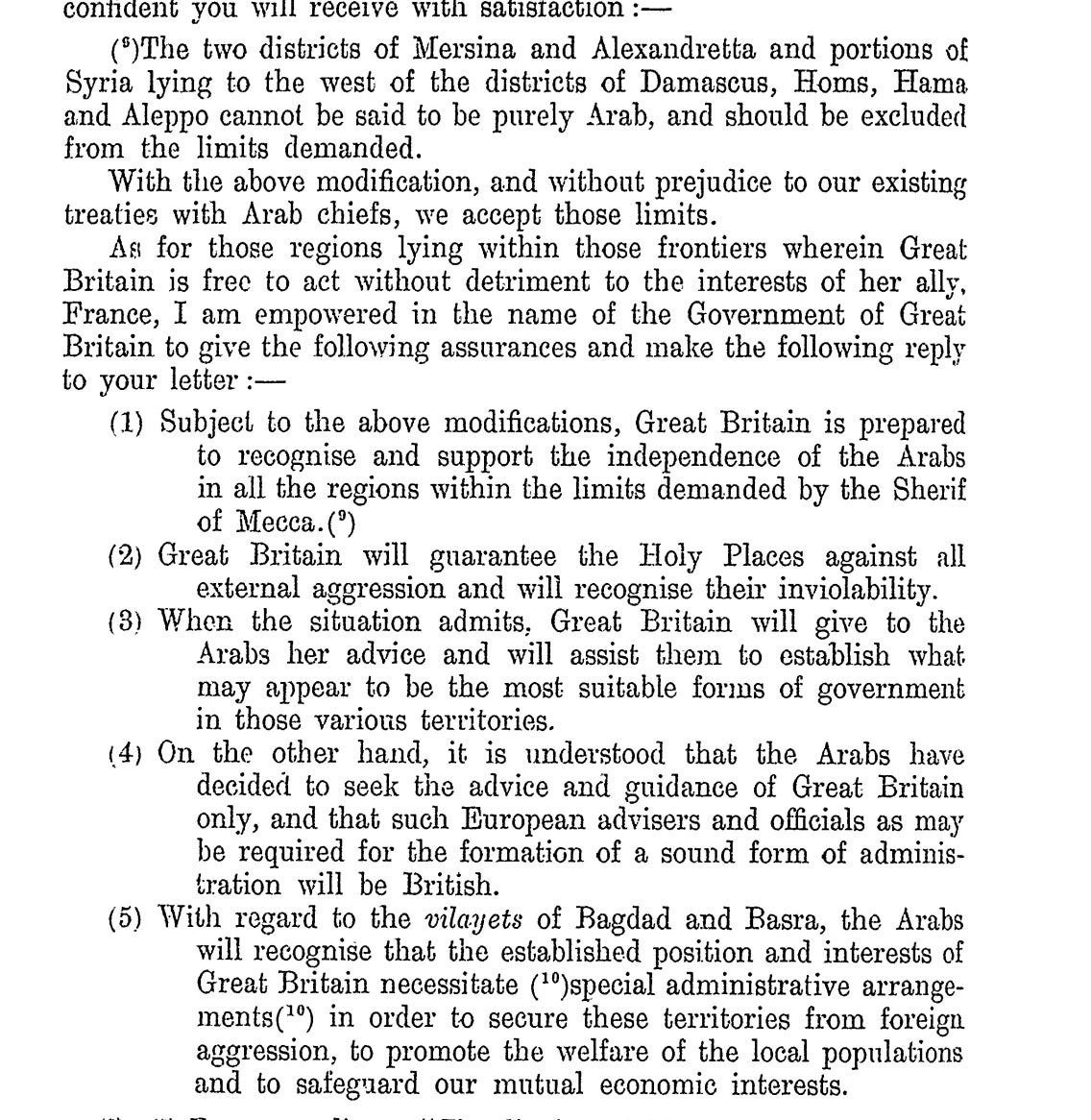

The boundaries proved the sticking point. Note that Sherif Hussein marks the Arab state as “bounded on the north by Mersina and Adana,” Persia to the east, the Indian Ocean to the south, and the Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea on the west, then back up the coast to Mersina. The British, while welcoming “the resumption of the Khalifate by an Arab of true race” (Aug. 30 letter from McMahon), nevertheless expressed reservations about the boundaries. Here is an excerpt from McMahon’s response on Oct. 24, 1915:

There is a lot we could say about this letter, beginning with the imperial aspirations expressed in the provision that any Arab administration would in fact be full of British advisors. But here is the million dollar question: Was Palestine included in those “portions of Syria lying to the West of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo” that McMahon exempted from the future Arab state? Let’s look at the map.

It is pretty obvious that the territory being demarcated by McMahon as “not purely Arab” is Lebanon, which had a substantial Christian population and was its own administrative district under the Ottomans.

Yet in 1917, for reasons best detailed in Tom Segev’s masterful One Palestine, Complete, the British government issued the infamous Balfour Declaration committing His Majesty’s Government to support the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.” Why? Segev makes a convincing, though counterintuitive, argument that an uncomfortable mix of antisemitism and philosemitism, far more than purely strategic concerns, fueled the declaration. I could never top his characterization:

The British entered Palestine to defeat the Turks; they stayed there to keep it from the French; then they gave it to the Zionists because they loved “the Jews” even as they loathed them, at once admired and despised them, and above all feared them. They were not guided by strategic considerations, and there was no orderly decision-making process. The same factors were at work when they issued the Balfour Declaration, their proclamation of support for Zionist aspirations in Palestine. The declaration was the product of neither military nor diplomatic interests but of prejudice, faith, and sleight of hand. The men who sired it were Christian and Zionist and, in many cases, antisemitic. They believed the Jews controlled the world.

Lloyd George, then Prime Minister, joined many Englishmen in feeling that the Jews were in a position to determine the outcome of the First World War in three distinct ways: 1. Financing; 2. Encouraging the Americans to join the Allied Powers 3. To control the direction of the Russian Revolution. It’s important in this sense to understand the Balfour Declaration as one of many secret agreements that were made in wartime, most of which did not come to fruition. What made Zionism unique was not merely the movement’s organization prowess—which ensured this wartime promise would be kept—but something a bit darker as well. Here is Segev once more:

“Away behind all the governments and the armies there was a big subterranean movement going on, engineered by very dangerous people,” John Buchan wrote in his classic spy novel Thirty-nine Steps. The director of information for the British government during Lloyd George’s administration, Buchan was talking about the Jews. They pulled the strings of war in accordance with their interests, he had one of his characters say: “Things that happened in the Balkan War, how one state suddenly came out on top, why alliances were made and broken, why certain men disappeared. . . . The aim of the whole conspiracy was to get Russia and Germany at loggerheads.. . . The Jew was behind it and the Jew hated Russia worse than hell.... The Jew is everywhere ... with an eye like a rattlesnake. He is the man who is ruling the world just now and he has his knife in the empire of the Tsar.” Chaim Weizmann did his best to encourage that impression.

Of all the ideas that are difficult to grasp today, the fact that Zionism has long depended on the support of antisemites is near the top. In this sense, the contemporary dependence on Christian evangelicals represents continuity, not rupture (I pointed this out a number of years ago and was rewarded with a record amount of hate mail).

I think there is a lot of room for debate about the nature of the Zionist movement prior to earning British imperial support, but afterward, it was undeniably tied to the advance of empire. From Weizmann to our own time, Zionists have appealed to Western powers by promising to serve as a civilizing vanguard in the region - or bulwark against Eastern barbarism. Israel changed imperial patrons some decades ago, but many of the dynamics I examined in my book about Mandate Palestine remain, right down to imperial frustration over the behaviour of the vassal state. At some point down the road, I’ll have to say something more about the realities of British control over Palestine during the Mandate period and how it—not merely Jewish bravery and genius—facilitated Zionism’s success.

We know what happened to Palestine, of course, but what about the rest of Sherif Hussein’s Arab state? How did we end up with a collection of nation-states with oddly drawn borders instead? I’ll continue with that part of the story next time.

In the meantime, I’m very glad to share a long piece I wrote over the summer for Jewish Currents, newly released from the paywall. It tracks career of National Conservatism founder Yoram Hazony and the uncanny ways that Israel has become the template for increasingly illiberal politics on the global stage.