A while back I opened a thread for questions about the current crisis in Palestine and Israel, and I finally have enough breathing room to get to them. Today I’m going to tackle two massive questions from readers (on the origins of Palestinian nationalism and the Jewish v. Palestinian “right of return), with a plan to turn to Hamas, violence, and the role of Iran in regional politics next week. If you have a burning Small Talk question I haven’t addressed yet, please leave it in the comments and maybe we will go for Round 3.

There’s so much that’s been said about the origin of the Palestinians as a nation. When were they formed as a nation? Could you tell me a bit about their self determination as a people?

There are two distinct points we have to take up here: 1. When and how did there emerge a distinct sense of Palestinian identity tied to a nationalist political project? And 2. What’s at stake in these debates over the existence of a Palestinian people?

As for #1, historians generally date the origins of Palestinian nationalism to the early 20th century. As Rashid Khalidi has shown in his book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, references to filistin (the Arabic term for Palestine) go back many centuries, but the idea that the Arabs of Palestine across religious lines were members of a common national community really dates to the first decades of the 20th century. If this seems rather recent to you, please remember that nationalism was not the normative political form until after the First World War. As I’ve charted in my WWI series, one of the casualties of the war was the imperial land empire model (Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian) which was not organized around the presumed homogeneity of ‘the people’, but rather the enormous diversity of languages, customs, religions, ethnicities, etc. The nation-state model has become pervasive over the last century, but that should not blind us to the fact that there have always been other ways of conceiving of the political community. Similarly, again as Khalidi has shown quite convincingly, the idea that identity was singular itself is a rather recent innovation. In contrast, we find Palestinians in the early 1900s referring to overlapping identity categories: of being Arab, Palestinian, Ottoman, a Khalili (resident of al-Khalil aka Hebron), and Muslim, for instance, without any sense that these were contradictory or mutually exclusive identifications.

From Kâtip Çelebi's mid 17th century map of the Ottoman Empire, showing “ard al-filistin” (the land of Palestine)

How then did a distinct sense of Palestinian identity emerge? We can speak broadly of two major influences. The first was the general diffusion of nationalism as a way of constructing what Benedict Anderson called “imagined communities” — most often premised on the idea of an unbroken chain between a people’s glorious past, fallen present state, and potential but yet unrealized greatness. If this sounds like theology to you, you’re not mistaken. Beginning in the mid 19th century, Arab intellectuals from North Africa, Egypt and the Levant began to engage contemporary European political thought in earnest, mixing it with aspects of Arab and Islamic culture to create a new, modernizing amalgam. The best book about this is still Albert Hourani’s classic account, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age. The resulting political and social movements (the Arab nahda, renaissance, and Islamic Modernism), embraced the glorious past-present degradation-future redemption model outlined above, and posited that national revival depended on a return to the roots of Arab-Islamic civilization. The Turkish-speaking Ottoman leadership came under particular fire from these modernizing intellectuals, who attributed the degradation of the Arab nation to the yoke of Turkish despotism (you may remember this from my WWI post how the idea of the Arabs as a glorious people-in-waiting fueled British support for their cause).

All of this is to say, there was prior to the First World War an emerging sense of Arab national identity that was 1. cross-confessional (Arab Jews were very much a part of this process too, as we know from anthologies like this) and; 2. highly critical of the Ottoman Empire’s authoritarian rule, particularly given that this was the era of “Hamidian despotism,” wherein the Sultan suspended the constitution first adopted in 1876. Yet, prior to WWI, the dominant agenda of nascent Arab nationalist movements like al-Fatat was for greater decentralization of Ottoman rule/Arab autonomy, not political independence. But after the war, as I’ve chartered in the post about the movement to found a united Arab state, the emphasis very much shifted toward one of advancing Arab independence and fending off British and French colonial incursions.

Palestinians played an active part in the General Syrian Congress that convened in Damascus from 1919-1920, but were forced to quickly pivot by the imposition of a French mandate on Lebanon and Syria, and British rule over Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq. It was through the parceling of territory to European countries via the instrument of the League of Nations mandate system that the present national borders in the region came to be. And it did not take long for the partisans of Arab independence within these newly-created states to redirect their energies in this changed context toward achieving independence for the new national units (e.g. Lebanon, Syria, Palestine) rather than the Arab people as a whole. It all moved very quickly, and in the space of a decade a Palestinians went from Ottoman rule, to the promise of Arab unity, to the more localized struggle for independence against British and Zionist forces.

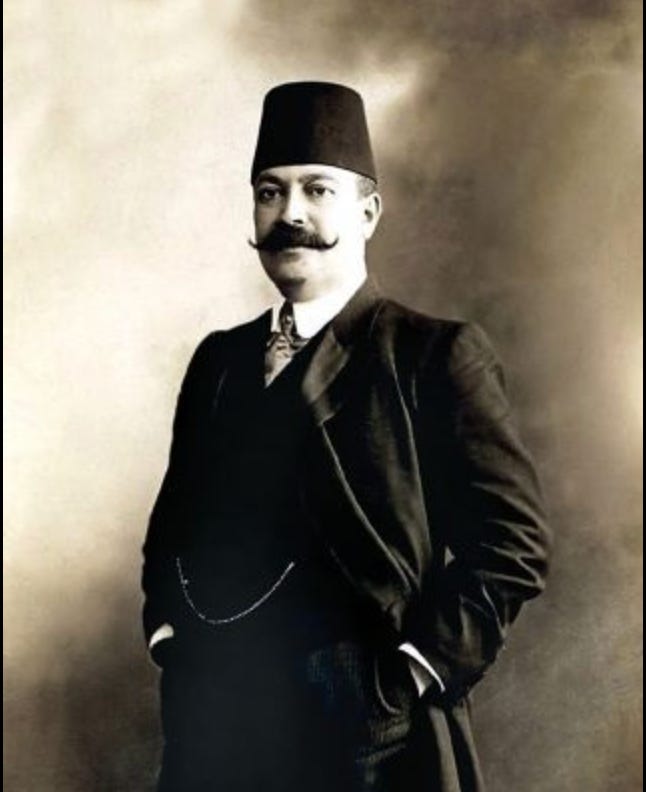

That brings us to the second major force in the emergence of Palestinian national consciousness: the confrontation with the Zionist movement. Already in May 1911, three Palestinian representatives to the Ottoman Parliament (Ruhi al-Khalidi, Hafiz Sa‘id, and Shukri al-‘Asali ) warned that the government was not taking seriously enough the risks presented by Zionist colonialism. After the war and Faisal’s defeat, Palestinians became intently focused on organizing across Muslim-Christian lines to protest the imposition of the Mandate and lobby for representative institutions. But they were hamstrung by the terms of the Mandate, which itself reflected the views of Western statesmen that there was no Palestinian people whose wishes required consideration.

Ruhi al-Khalidi

Recall that the Balfour Declaration—which was incorporated into the Mandate for Palestine—spoke only of protecting the rights of “non-Jewish communities,” i.e. there was no sense here of a Palestinian people, but only different religious communities of Muslims, Christians, Druze, etc. Zionist leaders too disputed the idea that Palestinians were a nation on par with their own: they saw only a hodgepodge of different groups, not a ‘real’ people that was worthy of self-determination. As I detail in an earlier work, when Palestinians tried to mobilize on national lines during the Mandate period, they were told by British officials that they could only achieve autonomy at the level of the religious community. And as Khalidi has shown in another work (in The Iron Cage), the upper-class Palestinian leadership from this period (the notables) proved completely ineffectual in creating the sort of mass mobilization that would counter these sectarian tendencies.

It was truly the experience of shared trauma in 1948 that cemented Palestinian national identity, which received a further boost after the 1967 war. It was only then that Palestinians living inside Israel could reestablish direct relations with those in the West Bank and Gaza; ironically, the Israeli occupation fueled the sense of shared national experience and common national future. It was also in the late 1960s that the PLO (which was originally established by the Arab League to contain Palestinian aspirations) became more genuinely representative of the masses with the first crop of leaders who did not come from the old notable families, and who consciously eschewed the sort of sectarianism that undermined Palestinian unity under the Mandate.

This brings us to point #2: There have many unconvincing attempts to read this history backwards and establish some sort of primordial Palestinian national sentiment. We should resist this urge, but also understand why it exists. What’s really at stake here is that we have, for over a century, lived in a world in which having rights and exercising self-determination can only be done by “the nation” acting as a unified whole. This is what’s behind the continual insistence by Zionists—from Ben Gurion and Golda Meir down to the present—that “there are no Palestinians.” If Palestinians can be shown to fall short of the proper criteria of ‘real’ nations, the thinking goes, they can’t complain about being turned out of their country by a group with more established national pedigree. But we can see how absurd this logic is by asking the following question: Even if we were to be able to show definitively that Palestinians did not think of their identity in national terms until after 1948, would that fact make their expulsion and dispossession any more acceptable? Rather than leaning into the logic of nationalism, I think we need to think more critically and expansively about the criteria according to which we grant people rights.

Would you kindly clarify distinctions between the Israeli and Palestinian rights to return (prohibitions/permissions, etc.).

UN Resolution 194 was adopted in December 1948, by which time most of the approximately 750,000 Palestinians who were expelled or fled the war had been displaced. It resolved that:

refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.

But the Israeli cabinet had already decided the prior June, still in the early months of the fighting, to prevent any Palestinians who had fled from returning to their homes. This was done for obvious demographic reasons: In 1947, there were more Palestinians (489,000) than Jews (407,000) living in the territory that the UN demarcated as the future Jewish state. However much they would deny it later, it was obvious to Israel’s leaders that they would have to overturn this demographic reality, and this realization fueled both the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and the refusal to comply with UN Resolution 194.

It’s noteworthy that we know much of what we do about the expulsion of Palestinians, or Nakba, from the Israeli historian Benny Morris whose 1988 book and later research has confirmed via archival evidence was was long documented only by oral testimony. Morris is no lefty, and he not only insists that expulsion in 1948 was necessary, but that the Zionist logic barring a Palestinian right to return remains sound. In an essay published just over twenty years ago, he gave voice to this sentiment and to the frankly racist and Islamophobic ideas at its core:

This argument is as valid today as it was in 1948. Israel today has five million Jews and more than a million Arabs. Were 3.5 to 4 million Palestinian refugees - the number listed in UN rolls - empowered to return immediately to Israeli territory, the upshot would be widespread anarchy and violence. Even if the return were spread over a number of years or even decades, the ultimate result, given the Arabs' far higher birth rates, would be the same: gradually, it would lead to the conversion of the country into an Arab-majority state, from which the (remaining) Jews would steadily emigrate. Would Jews really wish to live as second-class citizens in an authoritarian Muslim-dominated, Arab-ruled state? This also applies to the idea of replacing Israel and the occupied territories with one, unitary binational state, a solution that some blind or hypocritical western intellectuals have been trumpeting.

Those western intellectuals notably included the late Edward Said, who died in 2003 and had become one of the most forceful advocates for a single, binational state in his later years. Binationalism, which was originally championed during the Mandate period by Martin Buber and Judah Magnes, has indeed become the favored solution among many academics (present company included), though it has never gained mass support among either Israelis or Palestinians. According to 2022 polling, only 20% of Israelis and 23% of Palestinians favored a single, democratic state. More of each group favored an unequal one-state solution, i.e. for Israelis, the continuation and codification of present conditions; for Palestinians, a sort of role reversal with themselves in the stronger position.

As for Israelis, the Knesset passed the Law of Return in 1950, which stipulated that “Every Jew has the right to come to this country as an Oleh [immigrant].” There have been two amendments, most recently in 1970 which extended citizenship rights to non-Jewish spouses, children, and grandchildren and their spouses (this was done in the wake of increased immigration of Jews from Poland, many of whom were assimilated and intermarried). There has been endless debate about who is a Jew—the Orthodox criteria is having either been born to a Jewish mother or undergone an Orthodox conversion—but the state has embraced more expansive criteria. It has long allowed foreign converts to non-Orthodox denominations access to Israeli citizenship (until 2021, the conversion had to occur abroad), and was eager to accept nearly a million Soviet Jews despite many of them not being Jewish according to the Orthodox definition. Given the ongoing demographic war with the Palestinians, it is easy to see why the state is willing to be far more lax than the rabbinate in determining who is a Jew.

The Israeli Law of Return is premised on the idea that never again should Jews face the situation that they did in the 1930s: trapped within countries looking to exterminate them, with nowhere to go. I’m sympathetic to the trauma and sense of insecurity that one finds at the root of this law, but I dispute the premise on several grounds. Zionists often engage in a sort of counterfactual and argue that the worst of the Holocaust would have been avoided had Israel already existed, had Jews somewhere to go. But there’s another counterfactual we can engage as well: the worst of the Holocaust would have been avoided had other countries been willing to absorb Jewish refugees. At a more fundamental level, the idea that security is best achieved by each people having their own little assigned square on the map is, I think, absurd. We live in multi-ethnic, multi-racial states—a fact that will only intensify in a global age—and we need an enforceable concept of human rights and dignity that assumes plurality, not homogeneity, as the basic fact of our existence.

In truth, I feel a lot of ambivalence about the idea of a homeland and about the very particular form of security nationalism purports to provide, and I have serious doubts that gathering the world’s Jews into a tiny strip of land is the best thing for our people’s continued survival and flourishing. Ethically, I find it repulsive that someone like me—with secure homes on two continents—should have the ‘right to return’ while Palestinian refugees and their descendants exist in a state of perpetual homelessness. Finally, I’ve always found the idea of Israel as the homeland of the Jews far too compatible with antisemitism to merit uncritical embrace. As I wrote many years ago already, “The idea that Jews belong not in their actual place of residence and origin but in the Holy Land was of course not a position that all Zionists subscribed to, either then or now. Yet it is not hard to see the very problematic logic that links such assertions to the sort of blood-and-soil nationalism that led to the destruction of European Jewish life.”

One final word about the question of return in a more philosophical register: I’ve spoken at length elsewhere about why I find any fantasy of rolling back the clock and setting the world in perfect harmony to be morally and practically indefensible. I won’t belabor the point here but will only say that I believe we have reached the limits of restorative political projects and need instead to focus our energies on sketching, in annoying levels of detail, a new vision for the future. I have come to believe that mourning and grief, perhaps paradoxically, are key to elaborating this future.