The ocean sitting between the United States and me is not enough to guard against election anxiety. I imagine some of you might be similarly unsettled. My gift to you is some reflections on the emaciated state of American democracy — on why, in short, every election is the most important of our lifetimes, and yet the country remains perched on the fascist ledge. In short, a little light reading while waiting for the returns to come in.

Interestingly, today is also Guy Fawkes day. My UK readers will know this day commemorates a foiled plot to assassinate the king and blow up the Parliament. Brits celebrate by drinking heavily, building bonfires, and robbing tired parents of their precious slumber setting off fireworks. The overlap is particularly auspicious this year given the threats of violence from armed Trump allies looking to disrupt voting and dispute the election results. There should be some sort of custom cocktail to mark the coincidence. My husband helpfully suggested the Powder Keg: Barrel aged rum, smoky infusion, and a dash of C4.

One bit of news before getting to the main event: I was asked by The Yale Review to contribute a short piece to a special folio on nationalism. Each of the authors were asked what, if anything, differentiates today's nationalism from its prior forms. I decided that my contribution should take seriously the claim that late 18th and 19th century nationalism was associated with self-determination, liberation, and the development of democratic states — and was thus, implicitly, “a good thing” as Martha Stuart might say. In Yoram Hazony’s book, The Virtue of Nationalism, he notes this history in an attempt to anchor his project in a more respectable political tradition than European fascism and its Zionist offshoots.

My essay argues that today’s nationalism differs from earlier forms by making identity preservation an end-in-itself, detached from other pragmatic political ends (e.g. war, empire, self-determination). A harder question is what differentiates the new nationalism from the old fascism? Here the line is admittedly thin, but I would argue that fascism is a theory of the state, not of the nation that dwells within it. This distinction might not be very meaningful in the end, as the new nationalists have signaled their preference for an authoritarian regime that is nationalist over a democracy composed of multiple ethnic and racial groups. What does that mean in practice? That the United States’s model of civic union among people of different backgrounds is an inherently flawed one that should be rejected in favor of the Israeli model based on the supremacy of a singular group, whose privileges must be violently defended violently at all costs. The former project might be imperfect, tenuously advanced, and liable to corrosion; but the latter can offer only perpetual insecurity to those inside the fortress, and death and dispossession to those without.

Turning back to the seemingly perennial crisis of American democracy, I’ve been reading Caley Horan’s excellent history of the U.S. insurance industry, Insurance Era. This may seem like a strange place to root a discussion about democracy, but stick with me, because Horan’s very lucid book documents how private power works both against and through public institutions to the detriment of us all.

In particular, Horan shows how the insurance industry launched an assault on the nascent American welfare state beginning in the late 1930s. FDR’s response to the Great Depression represented a massive expansion of the federal government with the creation of new agencies and programs designed to shield Americans from the vicissitudes of capitalism. Work programs like the CCC, WPA, and and CWA put millions of people to work — including my grandfather, who left the farm in western South Dakota to help support his family. More fundamentally, the New Deal order represented a political vision in which security was a public right,1 rather than an individual privilege accessible only to the well-off or “virtuous” working classes (who saved their pennies—just not in the banks that collapsed—or purchased insurance policies). Consider, for example, the kind of security/insecurity on offer in this advertisement from the 1920s that Horan includes in her study:

Here is privatized security in all its glory: the death of a breadwinner consigns his children to a life of misery in the orphanage. In contrast, Horan argues, “The New Deal had framed security as a right of citizenship.” Social Security, which advanced the radical premise that old people shouldn’t starve to death and that even orphans could receive benefits in the event of their parent’s untimely death, was the most obvious manifestation of this new vision of citizenship. But Social Security—while extremely popular among the public—also represented a threat to the insurance industry’s entire reason to exist. Who would buy life insurance products meant to guard against destitution if the state offered such baseline support? And what if the state expanded into other forms of insurance, like—shudder—healthcare?

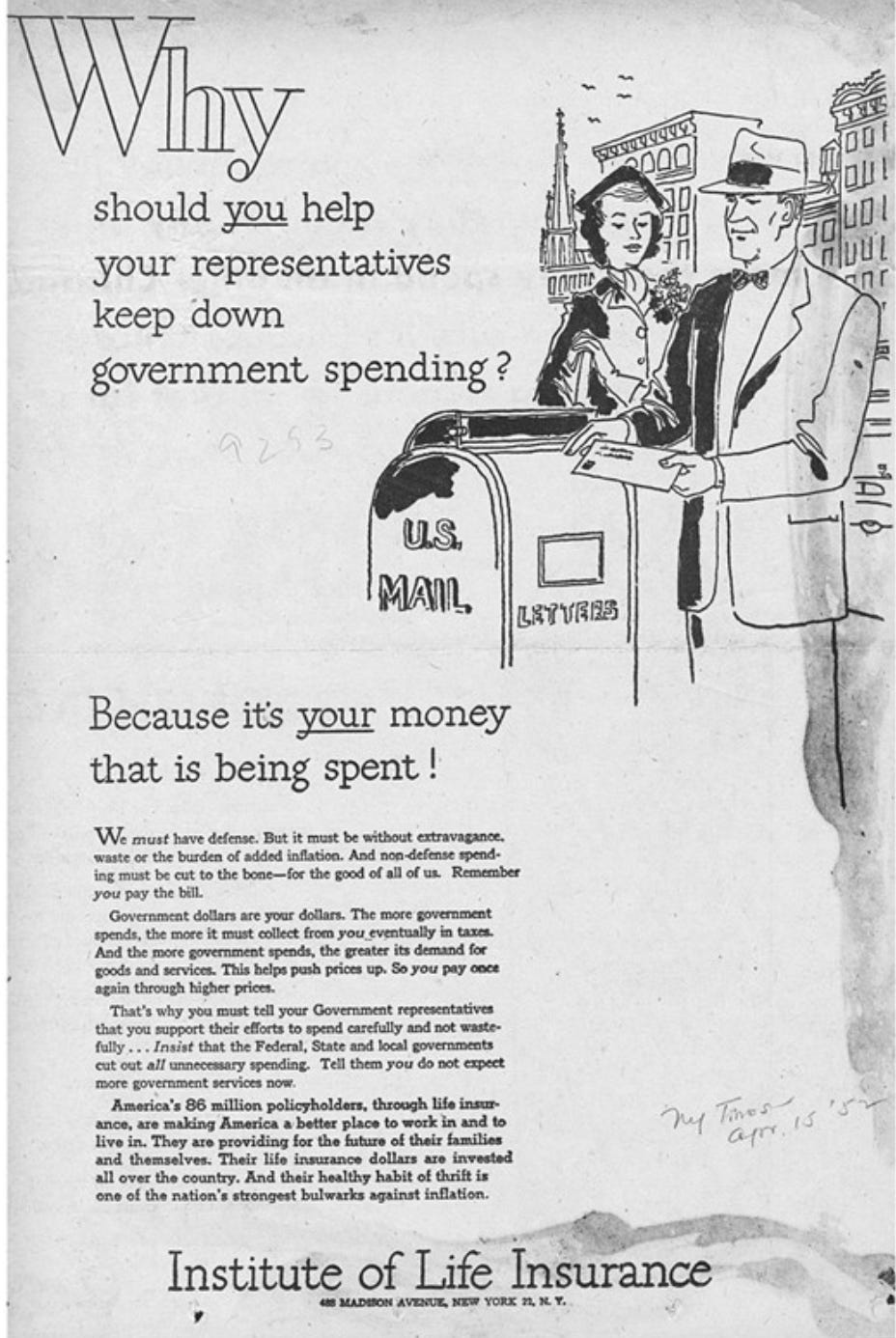

The insurance industry responded to the urgent threat posed by the emerging welfare state with one of corporate America’s first PR and marketing blitzes. This was part of a broader campaign to sell “self-made security” that extended into the post-WWII era, and that used what are now familiar (and tired) tropes about self-reliance. “By their own thrift and initiative, and by their own free will, 80 million men and women are using life insurance as a means of making their own security for the future,” as one advertisement proclaimed. In the Cold War ear, the messaging changed in subtle ways to stress private insurance as a vital part of the free enterprise system, and thus a patriotic roadblock to Soviet totalitarianism. Per Horan, “Instructing readers that ‘America is what it is because it sees more in the “do-it-yourself” spirit than in spoon-fed security,’ the campaign combined a celebration of free enterprise and entrepreneurial action with a thinly veiled critique of public provision.” Another post-war campaign stressed the need to oppose any continued expansion of government services. “Non-defense spending must be cut to the bone—for the good of us all.”

Importantly, Horan details how the insurance industry pioneered a form of corporate messaging aimed less at selling distinct products or services than securing an optimal political and regulatory climate. She also documents how confusing this was for employees of the J. Walter Thompson Company, then one of the country’s premier marketing firms, who could not understand why a company would throw so much money at “educational” material that did not try to boost sales.

But investing in ideology turned out to be very sound — just as it later was for the businessman who helped create the Chicago School of economics, whose thinking about deregulation, unemployment, market efficiency, and the role of government has revolutionized American life since the 1970s. Neoliberalism was and is many things, but one of them is an attempt to roll back the New Deal idea of collective security in favor of a society in which the market, not the state, is the optimal provider of all things - from education to housing and healthcare. One result of this shift was the return of the sort of crude, privatized security depicted in that 1920s insurance ad at the orphanage. Take, for example, this passage from Peter Bernstein’s 1996 bestseller, Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk:

Without life insurance, young families would have to turn to charity if their breadwinner were to die in the prime of life. And without health insurance, many more people would die before their time. Without fire insurance, only the wealthiest could afford to own homes.

It’s uncanny to feel like you’ve run in a circle to arrive back at pre-New Deal era arguments. What was propaganda for the insurance industry in 1950 had become common sense in the Clinton years. Whereas the 1920s ad came before the welfare state offered an alternative to privatized security, the industry and its allies have now spent several decades trying to convince people that there is no alternative to privatization. This has become particularly egregious in the battle against universal healthcare, which has been routinely touted as an onramp to communist revolution. These arguments have always seemed absurd, but it was only after reading Horan’s book that I understood how deeply rooted they are in the American insurance industry’s defense of its profits.

I won’t try to offer a comprehensive summary of Insurance Era—it’s very well written and well worth reading in full—but it’s worth noting one more thing about this industry: its remarkable success in undermining attempts to regulate it. As Horan notes, the passage of the McCarran–Fergusson Act in 1945 cemented a unique, state-based (as opposed to federal) regulatory structure for insurance. The industry lobbied heavily to maintain this structure, which sets it apart from the financial services industry and others that are controlled at the federal level. As she writes:

The complexity of the state-based system it cemented made it difficult for actors outside the industry—especially those seeking large-scale change on a national level, to intervene in insurance regulation. Industry critics hoping to pass laws that prohibited discrimination in insurance underwriting, for example, were forced to mount campaigns in every state. Lack of federal oversight also allowed insurers to pit states against one another, fostering competition among state governments to pass laws favored by the industry.

So the insurance industry has worked overtime to undermine the welfare state, minimize regulatory scrutiny, and maximize its profits. What has this to do with the crisis of American democracy? I’m always at pains in my work to stress that the crisis of democracy is a material one, not (per many liberal commentators) a loss of “faith” in democratic institutions. People lose faith in democratic systems because they fail to deliver the goods, as measured in actual governing capacity. In layman’s words, is the government able to do anything to make your life better, easier, or less stressful? To protect you from those who wish to take advantage of you or do you harm?

Take healthcare, for instance. Even if you enjoy—as I do—access to high-quality, private health insurance, it’s not a stretch to argue the U.S.’s healthcare system sucks. What’s important to note is 1: it sucks on purpose; and 2. it sucking undermines people’s faith in democratic politics as an arena to solve collective problems.

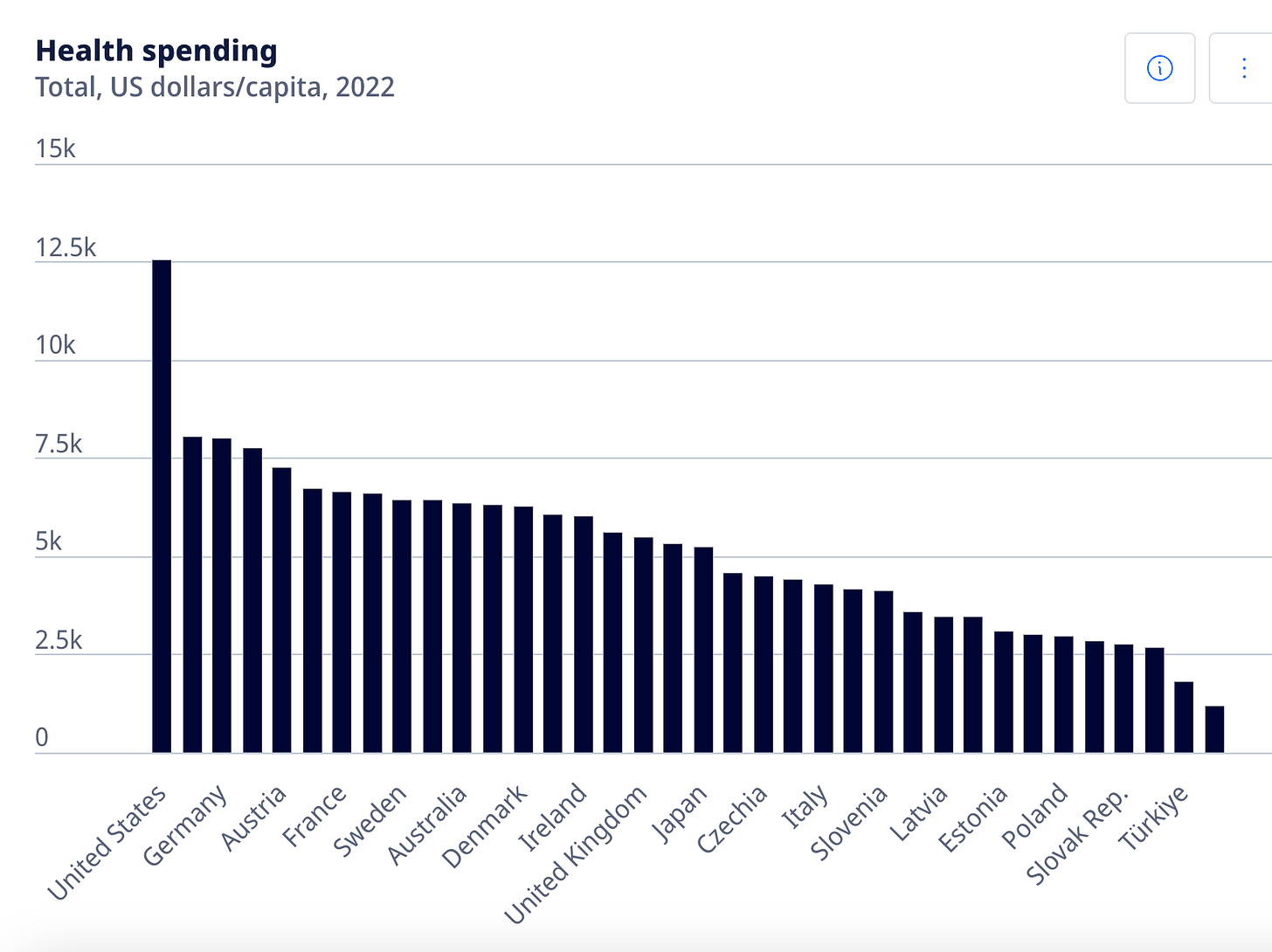

As Elizabeth Popp Berman has shown in another excellent study, neoliberal economic arguments were marshaled in the 1970s to undermine legislation proposing universal healthcare in favor of cultivating a healthcare marketplace that, proponents argued, would operate more efficiently than a public system. However, this theoretical efficiency has never manifested in empirical terms. Data indicate that the United States presently spends over $4000 more annually per capita on healthcare than other high-income countries, yet experiences the worst health outcomes across a wide range of categories: life expectancy, infant and maternal death, avoidable death, suicide, assault death, and frequency of multiple chronic conditions among adults.

A 2009 study found that nearly 45,000 annual deaths in the United State were attributable to lack of health insurance. And even after the Affordable Care Act expanded medical coverage, two-thirds of US bankruptcies still result from medical debt.

Horan’s book elucidates one of the key forces behind this quite terrible arrangement: that institutions meant to secure the public good have become the effective servants of the capitalist order they were meant to oversee. Scholars call this regulatory capture, and it’s just as apparent for dealings with the banking, tech, pharmaceuticals, and defense industries as it is insurance. The result is a civic order in which the government appears highly unresponsive to the policy needs of everyday people — leading to the observed gaps between public sentiment and actual policy. A recent example that caught my attention is the indifference that the state of Texas has shown to the people of Granbury, who have suffered a range of health ailments since a bitcoin mining operation opened nearby.

This sort of unresponsiveness is, quite simply, terrible for the legitimacy of democracies. It leads not just to apathy or cynicism (“these politicians are all the same and they’re all terrible” — hi mom), but fuels authoritarian alternatives. As I argued several years ago in Foreign Policy:

Setting aside superficial commonalities, what truly relates the U.S. far right to the Islamic State is the legitimation crisis that lurks behind each. Both movements are symptoms of a breakdown of “politics as usual,” and the destructive alternatives they offer have proven increasingly attractive to those exasperated by the dim prospect of change through traditional political means. These crises manifest in multiple ways: in anti-elite sentiment and attacks on traditional sources of authority, in faux-populist critiques not of power structures but of knowledge, in the allure of conspiratorial thinking, in the conceptual hollowing out of freedom and corresponding shift toward authoritarian governance, and in the embrace of violence as the premier mode of civic participation.

Not to be too glib, but this is the story of the American post-war political experience, one rooted in conservative attacks on the New Deal order, rapidly accelerated by neoliberalism, and repeated in industry after industry. It is why we face such massive levels of resignation and despair at a two-party system, both of which are determined to be the party of capital, and why even the most meager attempts at public oversight of powerful industries generate hysteria about “crippling innovation.”

We will never arrive at a more genuinely representative and responsive democracy without taming the role of capital in our elections and politics more broadly. Thus, perhaps beyond any single issue, at the top of my political wishlist is new legislation that dramatically shortens the electoral season, adopts public financing of elections, and effectively outlaws political action committees. So long as being a multi-millionaire or cozying up to lots of them remains a prerequisite for holding elected office, we will always be perched on the edge, looking out into the abyss, hoping that this time we don’t fall.

We should note that the definition of “the public” remained unjustly narrow, and that the full benefits of the New Deal order did not accrue to Black or Native Americans or women; by the time Civil Rights legislation came to dismantle many of these legal and structural impediments, the New Deal era was coming to a close.