Introducing Dr. Small Talk + An archival gem

"The political situation in Palestine is not very satisfactory"

I dream in paragraphs. Sometimes I get well-crafted sentence fragments instead, or qualifying clauses just awaiting their subject. It is usually around 4:30 am that I wake up with my thoughts, though I try to coax myself back to sleep (sleep is precious, I need a lot of it, and I have been perennially tired since having kids). But sometimes I give up, open my laptop and try to catch the torrent of words.

I need to write the way my children need to run around outside – to rid myself of pent-up energy before I burst. I’ve heard other writers describe this state as well, when the words are all queuing up in your brain. Some people smoke or drink or exercise to process the dismal flow of events around them. I write my way through, if never quite out. I offer these paragraphs of feeble justification for the sin of introducing yet another newsletter into the world.

Dr. Small Talk is both a joke (I’m constitutionally incapable of that form of polite banter) and homage to my mother. She once interrupted a lively debate about US foreign policy toward Iran by positioning herself at the head of the table and pounding on it repeatedly until silence fell. “At dinner,” she proclaimed, “we do small talk, nice talk, we talk about nice things like the weather. Small talk.” Unfortunately for my dear mother not even the weather is a bastion of safety these days. But perhaps I can be a better dinner companion if I have a separate outlet for my thoughts about history, politics, religion, violence, and everything else she has banned from the dining table.

This, dear reader, is what to expect: I’m going to aim for something of substance twice a month, with additional posts for paid subscribers. I am a historian by training and a teacher by trade, and this newsletter will reflect that. I am more comfortable with analyzing sources than offering pure punditry, and will usually bring a bit of text to unpack. This could be an archival document, a few paragraphs of scholarly work, or an advertisement. Though I have a PhD in Middle Eastern Studies, I am generalist at heart — drawn to far too many topics for a traditional academic career built upon hyper-specialization. You can expect to see all of them pop up at some time: contemporary politics, history, religion, philosophy, literature, and even the occasional film or television show. Thanks for being here - and now with no further ado - I want to introduce our first document.

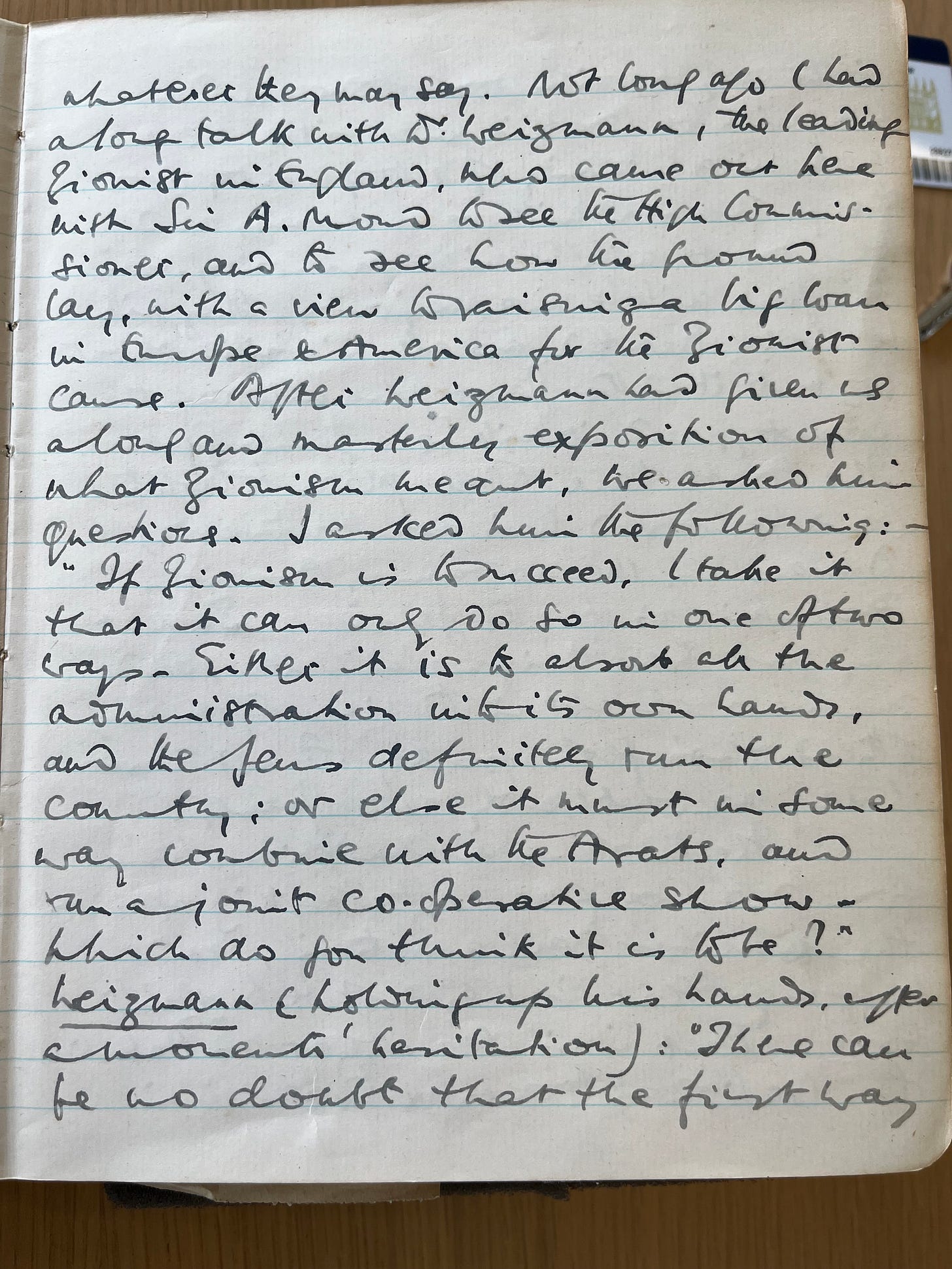

This is a diary entry dated January 30, 1921, from Humphrey Bowman, a British colonial official who was just beginning his long tenure (until 1936) as Director of Education for the Government of Palestine. All of Bowman’s diaries are at the Middle East Centre archive at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, if you ever want to pass your days trying to decipher someone else’s terrible handwriting. I first found this entry in 2010 while I was doing research for my dissertation about religious education in Mandate Palestine. I’ll offer a longer explanation down the line that details how Palestine ended up under British control following the First World War—that story has enough intrigue to deserve its own post—but for now I just want to look at this document a little more closely. Here’s a transcription of the juicy bits:

“The political situation in Palestine is not very satisfactory. Everything turns on one word ‘Zionism’ – the Moslems and Christians are afraid that Zionism means ‘Rule by the Jews, of the Jews, for the Jews – in Palestine,’ and that they, although in the large majority of 9 to 1 will be left out of the govt. and will gradually be deprived of their properties and rights. That this is not the intention of the League of Nation [sic] nor of H.M.G. [His Majesty’s Government] does not altogether affect the question, for it is undoubtedly the intention of the more advanced Zionists, whatever they may say. Not long ago I had a long talk with Dr. Wiezmann, the leading Zionist in England, who came out here with Sir A. Moud [?] to see the High Commissioner, and to see how his [?] lay, with a view of [??] in Europe and America for the Zionist cause. After Weizmann had given us a loud and masterly exposition of what Zionism meant, we asked him questions. I asked him the following: ‘If Zionism is to succeed, I take it that it can only do so in one of two ways. Either it is to absorb all the administration with its own hands, and the Jews definitively run the country; or else it must in some way combine with the Arabs, and run a joint cooperative show. Which do you think it is to be?’

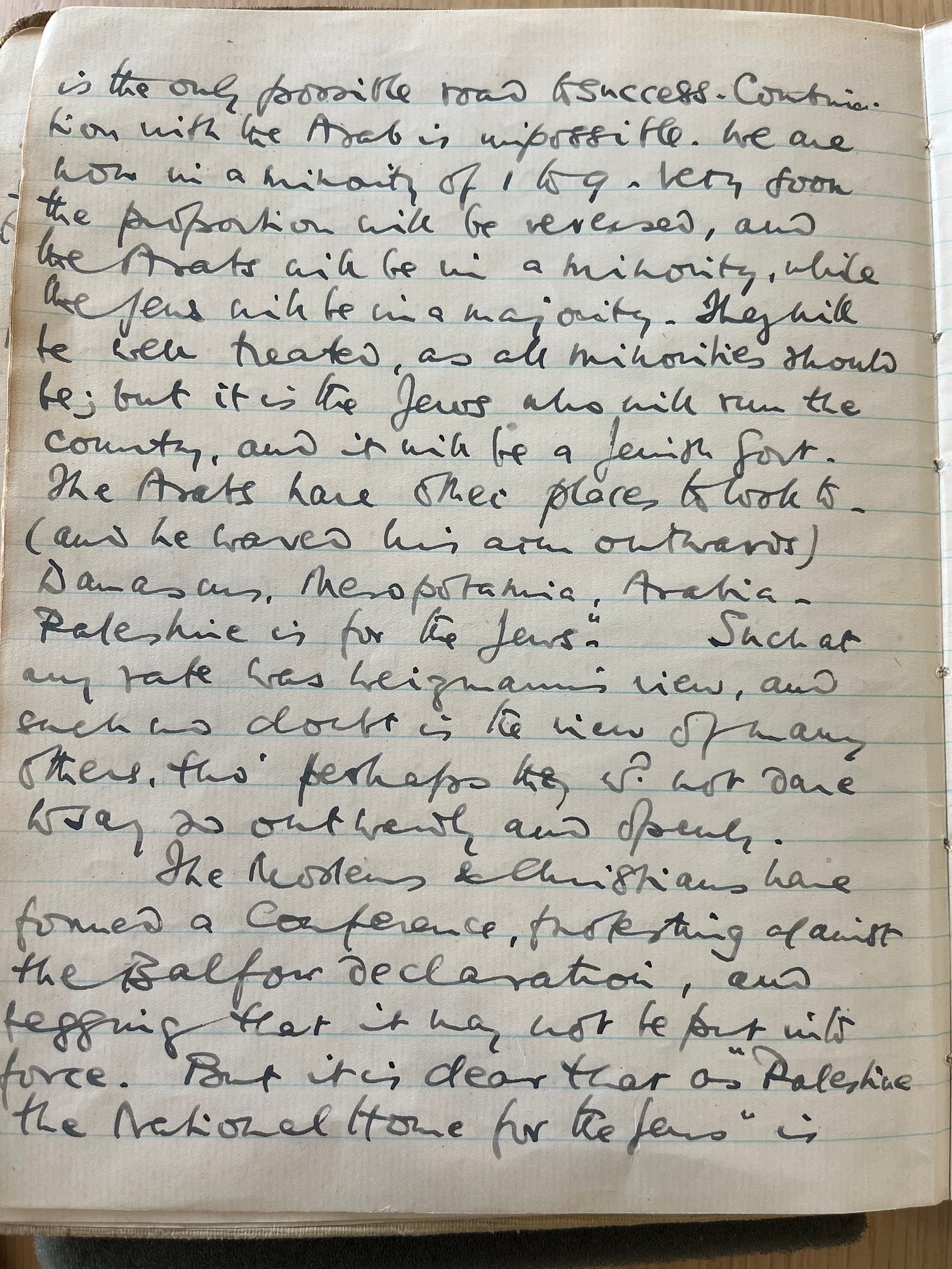

Weizmann (holding up his hands, after a moment’s hesitation): ‘There can be no doubt that the first way is the only possible road of success. Combination with the Arabs in impossible. We are now in a minority of 1 to 9. Very soon the proportion will be reversed, and the Arabs will be in a minority, while the Jews will be in a majority. They will be well treated, as all minorities should be; but it is the Jews who will run the country, and it will be a Jewish govt. The Arabs have their places to look to – (and he waves his arm outwards) Damascus, Mesopotamia, Arabia – Palestine is for the Jews.’

Such at any rate was Weizmann’s view, and such no doubt is the view of many there, though perhaps they do not dare to say so outwardly and openly.”

The diary entry is remarkable for a number of reasons, and I’ll address just a couple. First, it is extremely rare to find Zionist leaders from this period speaking so openly about their intentions. There was so much obfuscation—much of it purposeful—that deployed vague language in lieu of outlining what the political goal was. It’s important here to recall the precise language of the Balfour Declaration (itself intentionally vague): “His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” Note that it uses the language of “national home” and not that of Jewish state (which most Zionists did not use openly until much later), and also this bit of phrasing: "the establishment in Palestine of a national home” — suggesting it need not be all of Palestine, but merely in the country somewhere.

For their part, the British colonial administrators I studied were largely confused as to the policy they were supposed to be implementing in Palestine. Were they supposed to be creating separate Jewish and Arab enclaves or a single state? Many of them still couldn’t provide a clear answer to this question in the 1940s. In a 1944 memo commenting on the “tragic history” of education in Palestine, H. S. Scott of the Colonial Office wrote, “It is no doubt easy to be wise after the event,” but “if the purpose of the Mandatory was to establish a composite state one would have thought that unity of treatment in education should have been adopted from the beginning.”

Having no clear idea what they were doing or how it would work out politically, the British chose the time-honored tradition of muddling through. They never came close to the clarity of Weizmann’s language: the goal of Zionism was to render the Palestinian Arab population into a minority through a massive influx of Jewish migration that would transform the demographics of the country. The Arab population was not consulted, and their wishes were regarded as largely irrelevant (as Lord Balfour wrote in 1919, “The four great powers are committed to Zionism and Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desire and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land”). The Jews would control the government, and Palestinians who protested this reality should took to other Arab lands. Note that there is no notion of expulsion here — rather of minoritization. But still, it doesn’t age well!

Over the past seven weeks, the world has again been reminded of how “unsatisfactory” (to use Humphrey Bowman’s language from 102 years ago) the situation in Palestine is. Bowman’s option #2—that Jews will somehow combine with the Arabs of Palestine and run a joint show—still feels like an impossibility that is beyond the capacity of this generation of leaders. Many people are calling for change, for overturning the horrific status quo and creating a new reality on the ground. We certainly need alternatives, but we need them to be everything that British policy was not: transparent, consistent, and not least of all, just.

This is why I’m so tired of the slogans, and instead pose a series of questions: What does liberation or freedom or peace or security mean? What kind of state do you dream of? Who has a place within in, and under what terms? Give me the boring details. Do not say you’ll figure it out as you go along.

I’ll be back in a two weeks with a post about the First World War and the imperial context. And if you find yourself wanting to learn much much more, I should tell you I’m teaching my History of Modern Palestine class at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research online starting Jan. 21.

Is there a reason why your online course is closed? I understand not wanting to grade hundreds of papers, but auditing should be possible and give the Institute some additional funding.