Dear reader, I am sick and tired of this war, its horrific bloodshed, its saber-rattlers hoping to take the show on the road, and its spillover effects that have now even come for high school basketball games. But given that I can’t stop thinking about it, today I’m writing about—and truly against—the way that ideas about Jewish exceptionalism circulate and ultimately do harm. This requires directly confronting the thorny question of Jews and power — how we wield it, what it does, and what these practices can teach us about political and religious life more broadly.

The question at its core is a modern-day version of the question that has been asked in Jewish sources since the Book of Kings. Should the people of Israel aspire to be like all other nations? Or are they something apart, exemplary, or otherwise exceptional? This question has inspired ambivalence since it was first articulated — an ambivalence that Zionism exacerbated rather than resolved. Thus the attempt to found a Jewish state was often explained as a desire to normalize the Jewish people’s political, social and economic lives - to create a nation-state that would look more or less like those that emerged in Europe over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet Israel was also to be a “light unto the nations” — the Jewish state exemplary and the Jewish military moral. Today’s post will explore these contradictory impulses particularly as they relate to the exercise of Jewish political power. Let’s start at the beginning, shall we?

The elders of Israel approach Samuel to demand a king.

Source: The Morgan Picture Bible (c. 1250)

(1) When Samuel grew old, he appointed his sons judges over Israel. (2) The name of his first-born son was Joel, and his second son’s name was Abijah; they sat as judges in Beer-sheba. (3) But his sons did not follow in his ways; they were bent on gain, they accepted bribes, and they subverted justice. (4) All the elders of Israel assembled and came to Samuel at Ramah, (5) and they said to him, “You have grown old, and your sons have not followed your ways. Therefore appoint a king for us, to judge us like all other nations.” (6) Samuel was displeased that they said “Give us a king to govern us.” Samuel prayed to the LORD, (7) and the LORD replied to Samuel, “Heed the demand of the people in everything they say to you. For it is not you that they have rejected; it is Me they have rejected as their king. (8) Like everything else they have done ever since I brought them out of Egypt to this day—forsaking Me and worshiping other gods—so they are doing to you. (9) Heed their demand; but warn them solemnly, and tell them about the practices of any king who will rule over them.”

(10) Samuel reported all the words of the LORD to the people, who were asking him for a king. (11) He said, “This will be the practice of the king who will rule over you: He will take your sons and appoint them as his charioteers and horsemen, and they will serve as outrunners for his chariots. (12) He will appoint them as his chiefs of thousands and of fifties; or they will have to plow his fields, reap his harvest, and make his weapons and the equipment for his chariots. (13) He will take your daughters as perfumers, cooks, and bakers. (14) He will seize your choice fields, vineyards, and olive groves, and give them to his courtiers. (15) He will take a tenth part of your grain and vintage and give it to his eunuchs and courtiers. (16) He will take your male and female slaves, your choice young men, and your asses, and put them to work for him. (17) He will take a tenth part of your flocks, and you shall become his slaves. (18) The day will come when you cry out because of the king whom you yourselves have chosen; and the LORD will not answer you on that day.”

(19) But the people would not listen to Samuel’s warning. “No,” they said. “We must have a king over us, (20) that we may be like all the other nations: Let our king rule over us and go out at our head and fight our battles.” (21) When Samuel heard all that the people said, he reported it to the LORD. (22) And the LORD said to Samuel, “Heed their demands and appoint a king for them.” Samuel then said to the men of Israel, “All of you go home.”

There are numerous commentaries on this passage in rabbinic sources, but most do not focus on what for us is the key question: Are Jews right to adopt foreign political models? The original text is actually quite clear: kings are bad and you shouldn’t want one just because all the other nations do! There is, moreover, a sense of divine disappointment evident in the text, that asking for a worldly king represents a betrayal of God. Yet, resigned to the fact that the Jewish people are constantly misbehaving, God relents but instructs Samuel to issue a disclaimer about kingship: You won’t like it and I won’t come to rescue you.

In one of the few sections of the Talmud to address these verses directly (Sanhedrin 20b), Rabbi Eliezer says that the elders of Samuel’s generation were justified to ask for a king to judge them given the unsuitability of Samuel’s sons to lead, “But the ignoramuses among them ruined it, as it is stated: ‘But the people refused to heed the voice of Samuel; and they said: No, but there shall be a king over us, that we also may be like all the nations, and that our king may judge us, and emerge before us, and fight our battles’” (translation courtesy of Sefaria). In the 11th century CE, Rashi (the preeminent explicator of the Hebrew Bible) wrote in his commentary on these verses that “the matter was wrong, because they said ‘to judge us like all the nations’.” It was evident to Rashi that of this assimilationist impulse was misguided. Indeed, as Ishay Rosen-Zvi and Audi Ofir show in their book Goy, the rabbinic tradition sought to differentiate Jews from other peoples and cautioned against imitating the ways of non-Jews in everything from modes of dress to sexual relations (the problem with lesbian sex, Maimonides held, is that it imitates the customs of ancient Egyptians!). More recently, Orthodox rabbis in nineteenth century Europe condemned the Reform movement for adopting non-Jewish practices with relation to synagogue worship. And to this days, Jews who pray in more traditional congregations encounter a liturgy that underscores the idea of Jewish separatism - reminders that (as we say in Aleinu) God “has not made us like the nations of the lands.”

I’ll offer a somewhat sweeping thesis here: however much it builds off certain elements in the Hebrew Bible, this notion of Jewish differentiation is chiefly a rabbinic idea developed in diasporic settings after the destruction of the temple(s) and the loss of political sovereignty (perhaps it’s useful here to mention the rabbinic shunning of militarism—the beating heart of Zionism—as goyim nachas, the sort of foolish thing that only non-Jews do). It was the rabbis who created what we now call Judaism in the wake of catastrophic loss, with prayer standing in for sacrifice, the Torah standing in for the homeland. While the Torah itself reads as a unique national epic—with the Israelites chosen by God to bring monotheism to the world—I don’t see this as the same sense of separatism that courses through rabbinic literature and the liturgy.

But Zionism was born of rupture, not continuity, with the rabbinic tradition. It’s no surprise then that among its acts of insurgency was a plea for normalization, for assimilation into the political and social models that prevailed in nineteenth century Europe. Early Zionists would often speak about how the ‘normal’ course of national development had been subverted by discriminatory laws that channeled Jews into money lending, trading, and the professions, rather than allowing the majority of them to live as simple farmers. For Ber Borochov, the leading ideologue of socialist Zionism who tried (and in my opinion, failed) to forge a synthesis between Marxism and nationalism, Zionist settlement offered the opportunity to invert the Jewish class pyramid - which was lacking its broad base of agricultural and industrial laborers.

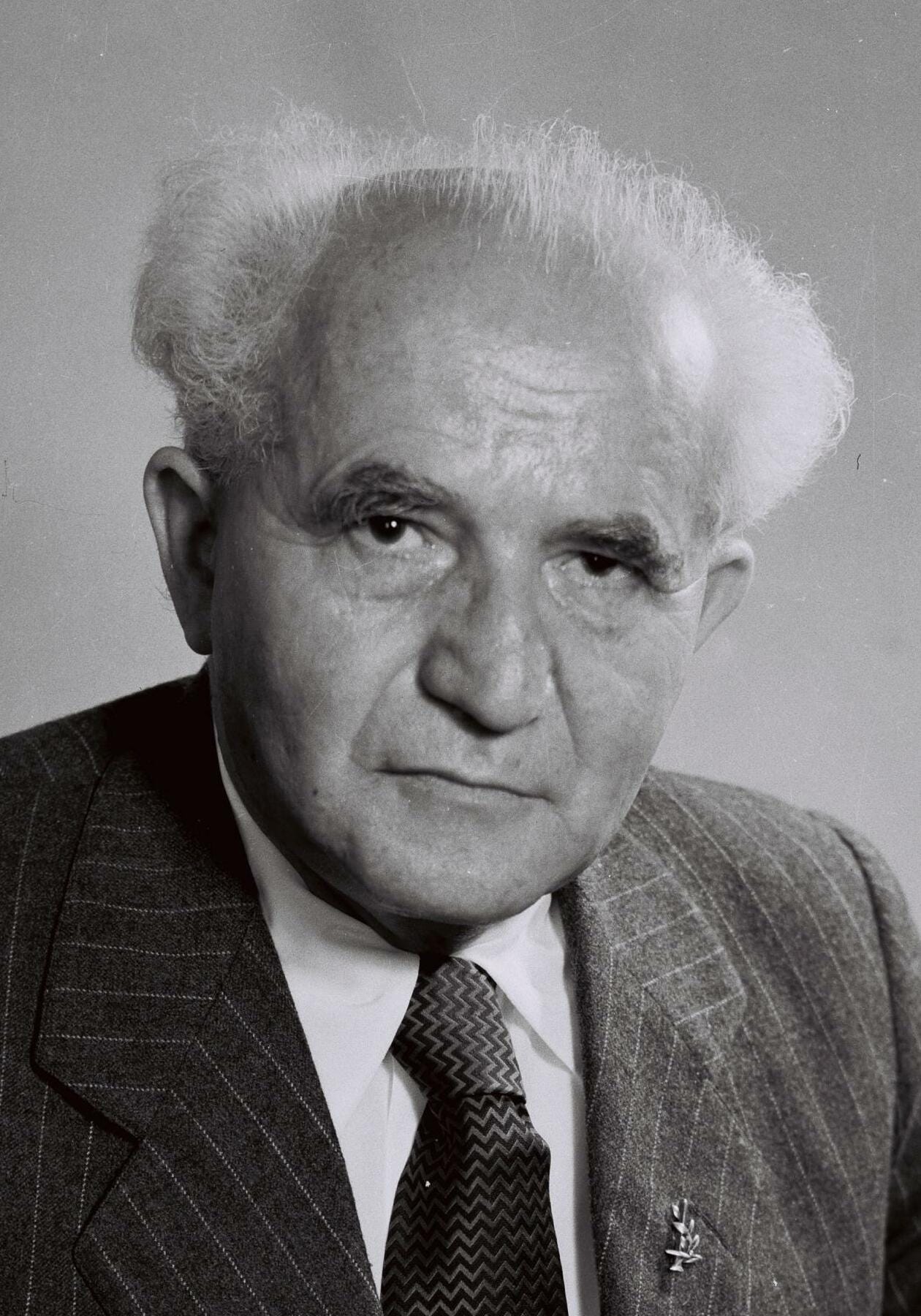

Yet even while pursuing the course of normalization, Zionism was never able to fully shake the older sense of Jewish separatism - which was increasingly spoken of as Jewish exceptionalism (the difference between these two terms is both excellent food for thought and more than I have time to explore right now, so you will have to forgive me for using them somewhat interchangeably). In an excellent article, Michael Brenner notes how these two impulses have rubbed up uncomfortably with one since the early days of the movement. In Herzl’s Der Judenstaat, the paradox appears in the dual attempt “to turn the Jews into a nation like any other nation, while at the same time entrusting them with a state that would serve as a model to all humankind.” Following the establishment of the modern state of Israel, David Ben-Gurion was still spinning these contradictory threads:

Two basic aspirations underlie all our work in this country: to be like all other nations, and to be different from all the nations. These two aspirations are apparently contradictory, but in fact they are complementary and interdependent. We want to be a free people, independent and equal in rights in the family of nations, and we aspire to be different from all other nations in our spiritual elevation and in the character of our model society, founded on freedom, cooperation, and fraternity with all Jews and the whole human race . ..

It’s been fascinating to watch these two impulses spring into action in the days and weeks after October 7. On the one hand: Israel has the right to retaliate for Hamas’s gruesome attack on its people because it’s what any nation would do, no country would accept the existence of a terrorist group on its border, etc. Yet this appeal to the conventional practices of states is not enough. Rather, Israel’s defenders repeatedly argue that the IDF is a “moral army,” its bombing campaigns undertaken with extraordinary care taken to not harm civilians. This is incredulous given the data available on civilian casualties, which, as I wrote about a few weeks ago, are disproportionately higher than compared even with Israel’s prior campaigns in Gaza. I could say a great deal about the cognitive dissonance between the IDF’s claims and the copiously documented reality, and how the denial of the latter is crucial to the maintenance of key Zionist mythologies. But I want to make a slightly different point: namely, why would any army behave in a morally upstanding fashion? Is that what armies tend to do?

The reality is that Israel is remarkably unexceptional in many regards: Its nationalist ideologies resemble others rooted in 19th century romanticism and 20th century fascism. Its settlers speak like American frontiersmen. Its attempted judicial coup followed a playbook pioneered by Hungary and Poland (with whom the Netanyahu government consulted). Its pogroms against Palestinians in the West Bank look a lot like the anti-Muslim violence perpetrated with tacit government support by extremist groups in India. Its systems of surveillance, indefinite detention, and Kafka-esque bureaucracy resemble those employed in American, French and British colonial and military occupations. Its bombing of Gaza looks like the Allied destruction of Dresden.

The hard truth is that states and armies are not moral entities, even though they may be necessary and very occasionally forces for good. They advance a logic that is at best amoral, which is to dominate, control, and pacify, even when they speak the language of freedom. Democracy offers the best shot of creating a state that does something better, but even democracies struggle to exert public control over the state’s use of violence (and Israel, as I’ll talk about in another post, has never been a liberal democracy). For me personally, knowing these things about militaries and the states that control them renders the idea of a moral state or moral army absurd. And given that position, the idea that one should tie one’s religious, ethical, and spiritual identity to a modern state and its use of violence has always appeared to me insane. Yet this is precisely what Jews have been told to do for the last seventy-five years. One cannot, I contend, have their moral exceptionalism and their nation-state too.

I want to write about one more instance of Jewish exceptionalism, this time closer to home: the Israel lobby. It’s an extremely difficult conversation to have because A. It all too often tips into antisemitic, conspiratorial screeds about Jews, money, and power; and B. It is readily apparent that organizations like AIPAC—which is reportedly planning to spend upwards of $100 million on 2024 congressional primaries alone—exert disproportionate influence on American elections and foreign policy. What’s always striking to me about this conversation, which often toggles between these two positions, is how disconnected it remains from others about lobbying and the sorry state of American democracy.

Here too Jews are not exceptional, but are rather playing the game like any other special interest group. Does the Jewish lobby exert any more influence than the pharmaceutical one that prevents the U.S. government from negotiating prescription drugs prices? Does it hold more sway than lobbies for gun and weapon manufacturers, finance, or insurance? Across the board Americans can’t have the nice things—gun control, universal healthcare, the eradication of predatory finance—that popular majorities want because the popular will does not find expression in our elected representatives. We all know this, which is why there is so much cynicism about participating in elections between the Party of Capital and the other Party of Capital That Says Nicer Things About Marginalized Groups. I think situating the Israel lobby and its outsized, anti-democratic power amid other special interest bedfellows is a better approach than leaning into Jewish exceptionalism, which in this case sounds quite a bit like antisemitism.

To the extent that Jews have been morally exceptional within the course of human history (I’ll leave the question of sacred history to others), it was largely a result of structural forces that positioned them oppositionally to systems of power. It is from the outside that one can best view the oppression, hypocrisy, and violence that are features—not bugs—of politics. It was because of their position as social outsiders that Jews embraced cosmopolitanism and advanced the causes of equality and genuine democracy. I know these ideals are hopelessly uncool in the days of nationalist hysteria. For me, they are the last vestiges of a Jewish exceptionalism worth saving and the only basis for real peace, whether in the Holy Land or our own.

On a mostly unrelated note, I’m pleased to share a new essay that I wrote for the New Statesman about the concept of risk and how we manage it - which Dr. Small Talk junkies will know is a subject I’m currently writing a book about. The piece chronicles my anthropological fieldwork at #Risk London (the UK’s largest risk management trade show), where I asked somewhat bewildered salesmen to opine on what the existence of their industry has to teach us about the state of our politics. I hope you enjoy!

Terrific article about a thorny subject. Thank you.